The 172 African-Americans of Margraten

February 23, 2018 by Megan Harris

The following is a guest blog post by Sebastiaan Vonk and Mieke Kirkels, historians in the Netherlands working to research, document, and commemorate the history of African American soldiers stationed in the Netherlands during World War II. Much like the Veterans History Project, their work ensures that the stories of veterans—particularly those whose voices have not been heard before—are preserved and remembered.

We encourage African American veterans who served in the Netherlands during World War II, or their families, to contact the Veterans History Project so that their stories can benefit both projects—as well as our collective understanding of war and society.

The 30th U.S. Infantry Division was the first Allied unit to cross the Dutch border near Maastricht on September 12, 1944. It marked the beginning of the country’s liberation. Later on, American forces would also participate in Operation Market Garden and engage in the liberation of the province of Brabant. However, it would take until May 5, 1945 until the remaining German forces surrendered. Today, the people of the Netherlands have adopted each of the 8,301 graves and 1,722 names of the missing soldiers at the cemetery out of a heartfelt gratitude for the sacrifices these soldiers made for their freedom.

However, until recently, little was known in both the Netherlands as well as in the United States about the contributions of African American troops to the liberation of the country, which had been occupied for five long years by Nazi Germany. In the minds of many Dutch people, U.S. liberators were white, even though 900,000 African Americans served in the U.S. Army alone, primarily in quartermaster, engineer, and ordnance units. The successful Red Ball Express, which was fundamental to the supply of frontline troops from August 1944 until November 1944, for example was mainly operated by African Americans.

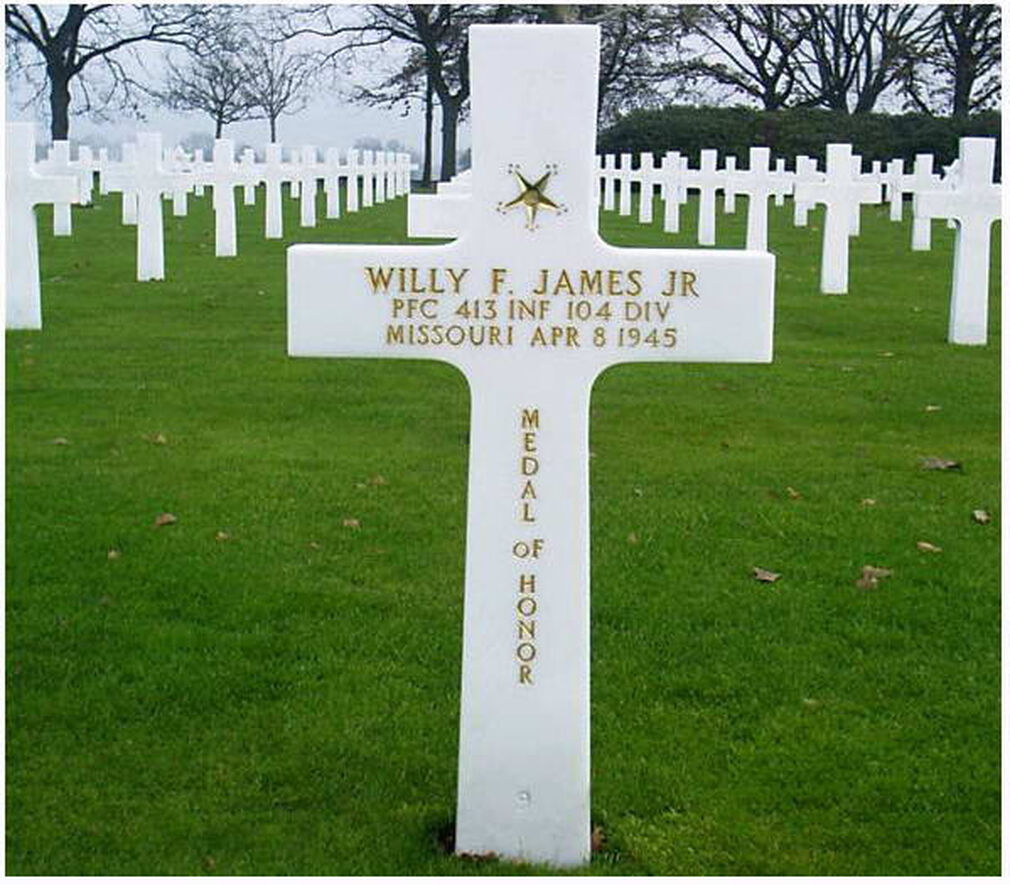

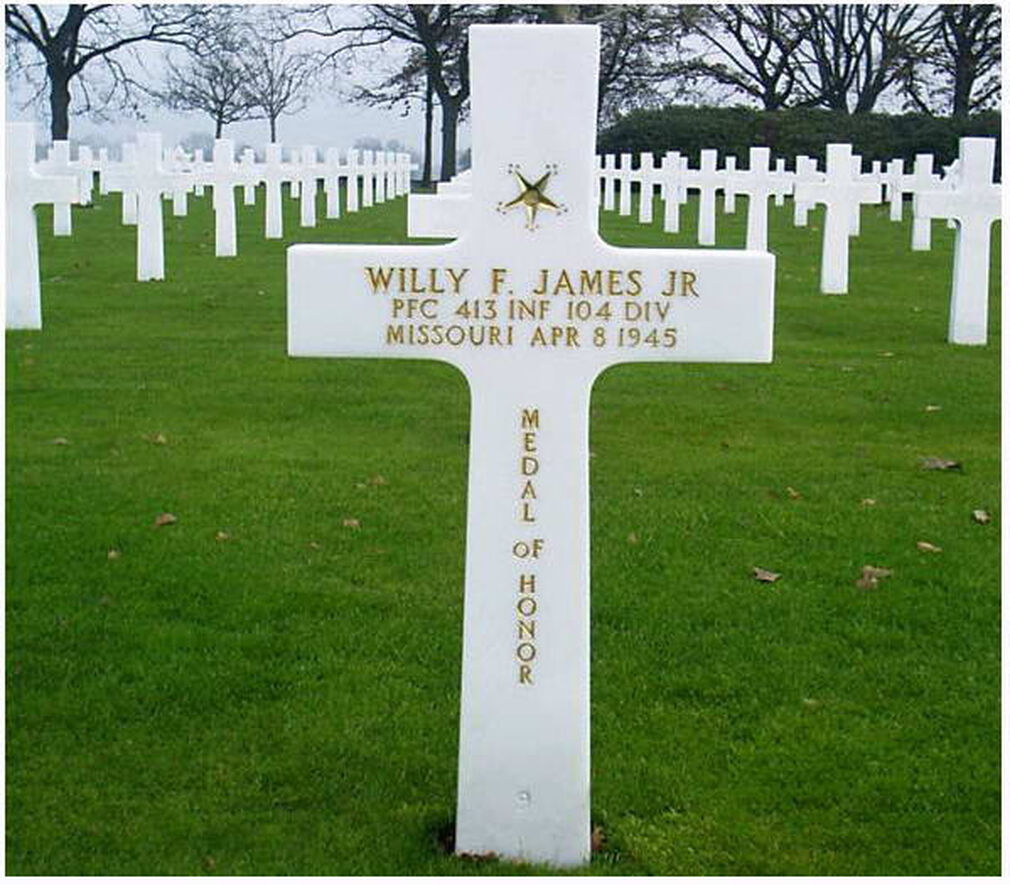

Moreover, although a rare exception in a segregated army, African Americans also served in combat units. For example, the well-known 784th Tank Battalion engaged in the liberation of the Dutch city of Venlo. A call for infantry volunteers at the end of 1944, led to the transfer of about 2,200 African Americans to infantry units. 45 of these “negro infantry volunteers” rest in Margraten.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s book on the 761st Tank Battalion highlights another dimension of segregation during World War II. When units were taken off the line, soldiers had an opportunity to take some time off in Rest & Recreation (R&R) centers; however, these facilities were restricted to white troops. The 761st Tank Battalion was forced to camp out on a meadow during their stay in the Netherlands. Nevertheless, the unit formed a soccer team and played matches against locals during their time off. The only R&R for black soldiers in the army was established just across the border in the Belgian town of Eisden in January 1945.

Change in public understanding of the role played by African American veterans in the Netherlands came about in 2009. An oral history project in the Netherlands on the construction of the American War Cemetery in Margraten uncovered a personal story of an African American soldier, Jefferson Wiggins, who had worked there as a gravedigger. He was one of the hundreds of African American soldiers who had buried the bodies of about 20,000 fallen soldiers, including those of other Allied countries and Nazi Germany. Trucks driven by African American soldiers brought the bodies there from the battlefields or temporary graveyards. The trucks full of bodies left a lasting impression on the local population.

However, stories of African American liberators of the Netherlands continue to be rare today. We believe that there are more stories out there, more stories that need to be told. To be able to paint a better picture of the stationing of African American troops in the Netherlands during World War II, we are looking for African American veterans, or their relatives, who are willing to share their recollections of their time in the Netherlands and their contribution to the liberation thereof. What were their experiences with the Dutch? Did they have contact with Dutch people? How was their relation with white American comrades? Did they participate in the daily festivities organized in villages and towns? Where were they housed? Do they have documents and/or pictures?

Likewise, we encourage relatives of the 172 African Americans who have found their final resting places in the Netherlands American Cemetery to come forward and share the stories about these men as part of efforts to document this history. And above all, to honor the service and sacrifice of those who were part of that history.

Indeed, the Netherlands seek to give long-due recognition to the African American soldiers for their contributions to the liberation of the country. As part of this effort, plans are being made to create an exhibition that highlights their contribution. The exhibition is scheduled to open in 2019, 75 years after the first U.S. soldiers crossed the border. A website and educational resources for schools will complement the exhibition. Your story will help us tell a part of the history that has been long untold.