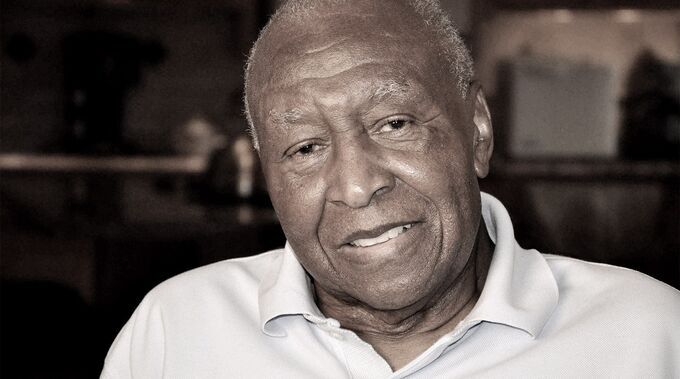

Jefferson Wiggins

Jefferson Wiggins was 16 years old when he was recruited in his home town of Dothan to go to Europe with the US Army.

The peasant family in which he grew up lived on the land that his father rented from a rich landowner. He hardly enjoyed any education. The Ku Klux Klan ruled the area where he grew up. For Jeff, the army meant an escape, not just from a poor life without any prospects, but especially from the racism he no longer wanted to endure.

In the autumn of 1944, the 960th Quartermaster Service Company in which he served as a Staff Sergeant, was sent to the Netherlands. There he worked for weeks, day in and day out, as a grave digger at the American cemetery that was developed in Margraten. That was from October 1944 on, immediately after the most southern part of the Netherlands was liberated. The American army was completely separated in black and white troops during WWII.

After 65 years, September 2009, Dr. Wiggins returned to Margraten for the first time and then discovered that practically no one in the Netherlands knew about the segregation in the US army that helped liberate our country. A segregation that was officially abolished in 1948. His memories of the three years in the segregated US Army are captured in the book "From Alabama to Margraten - memories of grave digger Jefferson Wiggins."

When the US Army prepared to go to Europe to help with the liberation, together with other Allied forces, it needed a lot of soldiers. In addition to calling conscripts, there was plenty of recruitment.

Before leaving for Europe, Jeff attended military training courses in, among others, Fort Benning. He left from there by train to the port of New York to be boarded there, along with thousands of others. While waiting for weeks for his unit to finally board, a volunteer at the New York Public Library helped him improve his reading and writing.

Jeff was 18 and a Staff Sergeant in the 960th Quartermaster Service Company when he set foot in Scotland after the troubled nine-day voyage. His unit worked there, along with thousands of other African-American soldiers, on the preparation of the major invasion on the European mainland, Operation Overlord, which started on June 6, 1944, D-day. African-American soldiers also landed on the beaches of Normandy, although the American media did not consciously pay attention to it. The US government did not consider that desirable. After a book written by Ulysses Lee 'The Employment of Negro Troops' just after the war, it took until the early 90s before extensive research was conducted in the US into the participation of African-American soldiers in the liberation of Europe.

In 2019, when American media paid attention to the 75th anniversary of D-day, African Americans were not mentioned.

In the Netherlands, however, Pastor Matthew Southall Brown Sr. represented the US Army later that year on August 31, during the official, national start of the festivities around 75 years of Freedom in Terneuzen. See Pastor Matthew Southall Brown Sr.

In January 1945, the white officers who managed his unit from one day to the next could not be found. Staff Sergeant Wiggins was forced to take over the lead. For that reason, he was personally named Second Lieutenant during a lightning visit by General Patton. Wiggins was therefore one of the first officers of color in the US Army.

Officer Wiggins returned to the US on January 25, 1946. Upon arrival in New York, he was warmly welcomed on the quay and congratulated by Black comrades who saw him, of the first 'one of us' with officer emblems. Not much later, on his way to his family in the south, from Washington DC, Wiggins had to take a seat again in the front part of the train intended for African-Americans, in the smoke of the locomotive. Despite his uniform and officer rank. German prisoners of war in the US got better places for whites in public transport than African-Americans at that time.

In his home town of Dothan, Wiggins received the High School Diploma after a while. In 1950 he was called up for active service as First Lieutenant and was sent to Korea (war against Japan). After returning, he worked for the Veterans Administration in Alabama and was active in the Civil Rights Movement, in particular in the fight for voting rights for African-Americans. He later studied political science at Tennessee State University. He wrote the book "White Cross, Black Crucifixion" about the experiences he had in the turbulent sixties as a director of social services at a college in New Jersey. He received an honorary doctorate and was elected in 2001 as Connecticut Multicultural Educator of the year.

A second book of him followed in 2003: 'Another generation almost forgotten'. The presentation of that book took place in the Pentagon. In 2007, Wiggins received the Meritorious Unit Commendation Award together with the other two living members of the 960th Quartermaster Service Company. In 2009 he was the keynote speaker at the annual graduation ceremony at the Military Academy in West Point N.Y. In September 2009, he returned to Margraten for the presentation of the 'Akkers van Margraten' oral history project on the occasion of the 65th anniversary of the liberation of South Limburg.

We recognized that smell, it was the smell of corpses

Wiggins back in Margraten after 65 years

In 2008, in anticipation of the celebration of the 65st years of liberations, a national project "Heritage of war - eyewitness stories" started. Mieke Kirkels, an oral historian, initiated with the local history organization of the municipality of Margraten (SHOM) the project 'Akkers van Margraten'(Fields of Margraten). The intention was to record what it had meant for the farmers in the region, to see their fertile fields change from one day to the next into a gigantic war cemetery.

In addition to farmers and other local residents, a number of white American veterans were interviewed in the US. The farmers told how hundreds of Black soldiers had been working as gravediggers on their fields, day after day. It was obvious that gravediggers also had to be interviewed for the project. It soon became apparent that they could not be traced. The archives in St. Louis where personal records of African-American veterans were stored, went up in flames in a major fire on July 12, 1973. Nothing could be found about them in Dutch archives. In the 1947 book 'Crosses in the Wind' by Captain Shomon, who from the beginning was in charge of the construction of the American cemetery, there are only a few short passages about the Black soldiers. Only in 2010 Wiggins heard about that book for the first time. After reading it, he said: 'As if we were only workhorses who were constantly thinking about food.' He knew all too well how people talked about African-American gravediggers at the time. Then he sighed and said, 'That's how it was those days.'

At the end of 2008, documentary makers Eugenie Jansen and Albert Elings in the US interviewed several white veterans who had worked in Margraten in 1944/47 for the oral history project. They also visited archives in an attempt to trace and interview gravediggers from that time. That remained without result. In January 2009, after they had returned from the US, a message from Mrs. Sherry Barbour of Georgia unexpectedly arrived via the website www.akkersvanmargraten.nl. She enthusiastically wrote how happy she was with information in English about Margraten. She was the caregiver of a veteran, Captain Solms, who had led grave diggers there in 1944. Two years earlier, in 2007, Solms turned out to have seen Jefferson Wiggins for the first time since 1945 during a military ceremony. The men exchanged telephone numbers. In January 2009, Mieke Kirkels could get in touch with Dr. Wiggins. Immediately a return trip to the U.S. for the filmmakers was planned to interview him.

In September 2009, on the occasion of the 65th anniversary of the liberation, both the Akkers van Margraten documentary 'Bitter harvest' and the book 'From farmfields to soldiers' graveyard' were presented, containing Wiggins' story about his time in Margraten. Wiggins as well as Captain Solms were invited by the municipality of Margraten to be present. There was a lot of publicity about Wiggins' return to Margraten. During a lecture at Center Ceramique in Maastricht, he faced a crowded room.

Wiggins was upset when he noticed that virtually no one among all those present and among all the journalists who interviewed him knew of the strict racial segregation that the American liberation army had divided into two organizations during WWII. He considered it his duty to the approximately 200 men of his former unit to share his memories of the three years he had spent in the segregated army. Those memories are recorded in the book From Alabama to Margraten - memories of grave digger Jefferson Wiggins (Mieke Kirkels, self published 2014).

Jefferson Wiggins died on January 9, 2013, before the book was finished. With the help of his widow Janice, the book could be presented in the Statenzaal of the Provinciehuis in Maastricht in November 2014. Janice Wiggins and their (grand)children were present. The U.S. edition of this book was published in March 2025.

Video in which Wiggins briefly tells about the 'fields of Margraten'.

1970

He wrote the book White Cross, Black Crucifixion about the experiences he gained in the turbulent 60s as a social services director at a college in New Jersey.

2001

Wiggins received an honorary doctorate and was elected as Connecticut Multicultural Educator of the year.

2003

A second book followed: Another generation almost forgotten. The presentation of that book took place in the Pentagon.

2007

Wiggins, together with the other two living members of the 960th QMSC unit, received the Meritious Unit Commendation Award.

2009

During the annual graduation ceremony at the Military Academy in West Point N.Y. Wiggins is the keynote speaker.

In the same year he was interviewed for the oral history project Akkers van Margraten. In September of that year he returned to the Netherlands for the first time, after 65 years.

17-12-2019 BBC World News Janet Ball about forgotten liberators https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w3csywyh.

Acknowledgement

Without Jefferson Wiggins, a significant part of the liberation history of the Netherlands would have remained unknown. Without him, the Children of Black Liberators could not have told their concealed history.