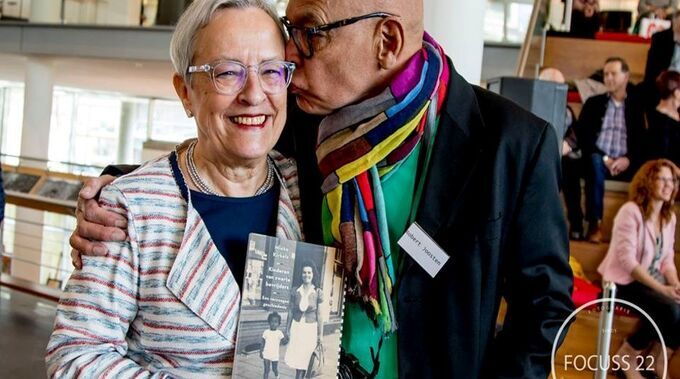

Robert Joosten

It was clear from the start I was not the milkman's son.

It was not sure who the father was of the baby Annie Joosten brought into the world in October 1945. She suspected it was not her husband, Jack Joosten, a constructional fitter, and the moment she saw her son she knew it wasn’t Jack. Seventy years later, her son Robert said, while laughing: ´it was clear from the start I was not the milkman's son´. And yet, Jack acknowledged the child as his son anyway. The couple got married in 1940. According to Robert, Jack was madly in love with Annie.

After the German occupation in the village of Nieuwenhagerheide, in the mining region of the Netherlands, Americans had been coming and going during the last months of 1944. Annie celebrated the liberation, just like everybody else in the village. The white GIs organized parties in a large site hut just outside the village. An eyewitness recounted how, as a young boy, he often saw 'rubbers' being thrown out the hut windows. The kids played with them, thinking they were little balloons.

In the village, Annie was a bit of an outsider. Her father worked at the electronics company Philips in Eindhoven for a while and the family had 5 children. Her son said that she was rather wild in the days of the liberation. Contraceptives were virtually unknown in the Catholic South, and the Roman Catholic Church even prohibited their use. The African American GI Annie must have been seeing for a while obviously did not use a 'rubber' or 'French letter' when making love to her, otherwise Robert would never have been born. And Annie would not have contracted an STD, a virus she transmitted to the baby, causing Robert's right eye to be slightly damaged since his birth

No matter how much Jack loved Annie, Robert thought they had a terrible marriage. ´Talking about problems was apparently not an option in those days, so he often beat her, but he never laid a finger on me.´ After ten years, the couple had another child, a daughter. Much later, Annie told her son she had been very unhappy in her marriage and for years tried to get a divorce. Jack blocked those efforts until she was 65. Annie died in 1992.

During an interview with Petra for Mieke Kirkels’ book, the name Robbie Joosten was mentioned for the first time. Petra and Robbie were in the same kindergarten and she was Black too. Once, when they came out of school together, she remembered Robbie's mother saying the two of them should get married one day. Petra had no idea where Robbie was. She thought of his mother as a somewhat eccentric woman.

A few months after Petra had talked about Robbie, Jos Sporken from Breda sent her an email. He attached a couple of pictures from his childhood in Nieuwenhagerheide, pictures from the Cub Scouts organization. In them is a small Black boy, grinning. Sporken wrote that he had taken out the pictures because he was gripped by the story Rob Gollin had published in de Volkskrant about Huub Schepers. Jos Sporken even remembered the little boy's name: Robbie Joosten. He was curious how Robbie was doing and wanted to get in touch with him. However, he did not have any leads.

When Paul van der Steen wrote a beautiful obituary for Huub Schepers in the NRC [Nieuwe Rotterdamse Courant (New Rotterdam Newspaper)] in January 2016, Robert Joosten contacted the NRC editorial board and so he heard about the oral history project. Robert was living in Amsterdam. In the first conversation, he spoke very candidly about his childhood, about his life as a Black boy in Limburg. He said he was hardly ever bullied. His mother's relatives were all very fond of him and he remembered an aunt as being a second mother to him. He hardly remembered hearing any comments about his skin color and his curly hair. 'Well, sure, I was called names sometimes, but that did not bother me.´ When he talked about his early childhood, it was clear those years were marked by the abuse his mother had suffered. He developed a keen watchfulness and was always alert to the fact that his mother could be hit by her husband.

As a young boy, Robert went to the police a few times when domestic violence was in progress. When he was twelve, he even climbed out the window in his pajamas once when the argument downstairs was getting too heated. He ran to the police station to get help. An officer went home with him just in time for Robbie to witness how his stepfather smashed a chair to pieces on his mother. A vicious scolding followed because he once again got the police involved. Robert: 'And still, Jack has always been nice to me, and Mom was proud of her dark child.'

Robert was the only one of the twelve people interviewed for this book who moved to the western, urbanized part of the Netherlands, the Randstad. Looking back on his childhood, he felt he often had to figure things out on his own, especially when it came to making important choices regarding his future. He missed out on getting guidance from his parents about the right direction. He left home when he was seventeen, and after dabbling in nursing, studying at the Rotterdam Dance Academy, and as a member of Scapino Ballet, he finally ended up as a prompter with the Amsterdam Stage Group (Toneelgroep Amsterdam). 'This job really suited me, playing a role in the background,' he said. Few of the people around him knew about his ancestry. In Amsterdam, Robert quickly made friends with a group of people from the theater world. He lived for quite a while at the home of Dutch comedienne Adele Bloemendaal, who has been, together with entertainer Wim Sonneveld and actor Henk van Ulsen instrumental in shaping his life.

Robert Joosten passed away in March 2024.