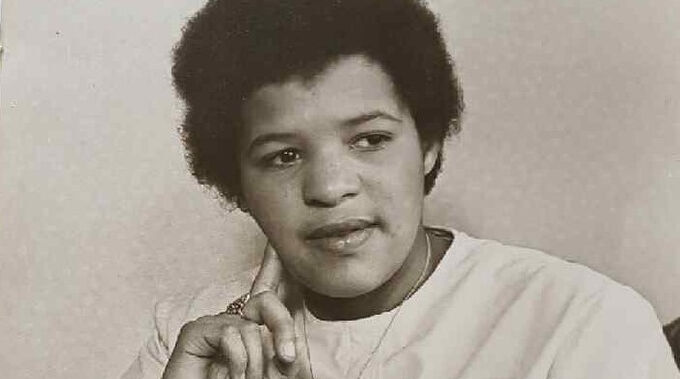

Rosy Peters

In August of 2015, someone at work questioned one of Rosy Peters' daughters, Maureen, about her tanned color. 'Well! You must have been on vacation in Spain, visiting your mother?' Maureen replied and told her coworker: 'Oh no, one of my grandfathers was a black soldier. My mother was a war baby.'

The coworker then referred to an article in de Volkskrant where Huub Schepers talked about having an African-American liberator for a father. Maureen sent the newspaper article to her mother in Spain. Rosy Peters and her husband Connie had been living there for a while but they regularly visited the Netherlands. Rosy would go there for doctor's appointments although mainly to see her children and grandchildren. After she read the article, Rosy immediately asked her daughter to contact Huub. About thirty years ago, Rosy and Huub met frequently under special circumstances.

Rosy was candid about her mother's unexpected pregnancy in 1945. 'It seems she actually had had a few boyfriends, at the time. After I was born, there was no money to

take care of my mother and me. The family assigned a man to the role of biological father, and went to court to make him pay child support. I still remember his name, he

was called Henri Brandon. He was from Surinam, twenty-five years older than my mother. During the time of the liberation, he worked as an interpreter for the Americans at the hotel where my mother worked as a chambermaid. According to my aunt Trees, he also lived there.' The court case came to nothing. Brandon denied being the father and had enough witnesses who were aware that Roos (Rosy's mother) indeed did have several boyfriends in those days. For years, that was all Rosy knew. 'Mother always reacted surly and dismissive when I tried to find out more about my biological father.'

Roos Heuts (1923-2002), Rosy's mother, was born on Kale Heide (Barren Heath) near Brunssum, Limburg. She was number eight in a miner's family of twelve children. Father Heuts was a Limburger, mother was Polish. They lived on the edge of a forest. At the time, the large family was well-known in the mining community. As a miner, father had a reasonable income, although with twelve kids, not every day was a feast. When dinner was on the table, everybody tried hard to quickly get their share.

The children started working at a young age. There was no money for secondary education. At the time of the liberation, Roos was working as a chambermaid at the Grand Hotel in Heerlen. This was a special location. During the war, it had served as the German headquarters, and after the war, the Allied generals gathered there, one time even including General Eisenhower. The hotel owners left after the liberation, their heads shaved.

On July 16, 1945, Roos gave birth to Rosy at the home of her older sister Trees. Not long after the birth of her daughter, Roos left for Amsterdam and started working at a cigarette factory. That way she earned a living for her baby and herself, even though Rosy stayed behind with aunt Trees' and her husband Willem's family. There, one kid more or less made no difference. Rosy: 'Once in a while, about every three or four months, a woman came to visit. To me, she was a strange woman.' Aunt Trees and uncle Willem were her mom and dad. Uncle Willem sometimes teased her and called her 'little coffee bean.' She remembered her mother and aunt having an argument at times, about her. At those times, Rosy's mother went against her older sister, and was not above mentioning that Trees received money for boarding Rosy.

She remembered being called names such as 'blackie' and 'negro', and she also heard people in the mining community tell her: 'You are a little American.'

Rosy attended elementary school in Brunssum, the Maria School. She was maybe six or seven, when her mother returned to Limburg for good. She had found a job at the ceramics factory in Maastricht. From the wooden community house at De Overberg, where she was living by then, she commuted to work. Rosy was living with her, which seemed only natural to mother Roos. The house was near aunt Trees' and uncle Willem's house, and any chance she got, Rosy went to see her 'mom and dad.' In those days, little Rosy stayed at a Fresh Air Fund home, in the seaside town of Egmond aan Zee twice, where she was treated for her asthma attacks. It affected her school performance and she was held back twice.

From early childhood on, Rosy had problems because of her different physical appearance. She remembered being called names such as 'blackie' and 'negro', and she also heard people in the mining community tell her: 'You are a little American.' Although she was always dressed beautifully, with a big white bow in her hair, she nevertheless felt she had been an 'accident.' She always felt inferior. As a child, her biggest wish was 'not to be black anymore.'

In class, she was constantly afraid of being skipped over. The teachers never asked her opinion. She grew up a very submissive, insecure girl. What did not help was getting reprimanded at home sometimes, and mother would say things like: 'I should have gotten rid of you,' or: 'I should have given you to the circus.' Circus people supposedly once had said: 'Just give her away, she is such a millstone around your neck.' But when her mother said these things, she would, Rosy remembered, always follow it with a: 'But of course I didn’t do that.'

When Roos started dating B., a factory worker at 'the ceramics,' Rosy's life changed once again. B. moved to Brunssum and started working in the mine, where the pay was

better. He moved in with Roos and Rosy. They continued to live in the community a while longer. B. said nasty things to Rosy when she had to repeat a grade: 'You're as

stupid as they come.' Or, if things were not going his way: 'I can have you placed in a home just like that, because you are not mine.'

One day, Rosy got dressed in an elegant outfit, with red shoes and a big bow in her hair. Mother was going to meet her boyfriend's relatives, who were obviously of a

higher social class than hers. Rosy could still hear their reaction when they saw her for the first time: 'She's a pretty child, too bad she is black.' From that moment on, Rosy

refused to come along on visits to her stepfather's family.

Mother married B. on September 17, 1953, and Rosy was legally recognized as his daughter. They moved to Maastricht. In the beginning Rosy was relatively happy

while living with her mother and stepfather. That changed when she hit puberty. Then, her stepfather started molesting her, and continued to do so for years. During that time, Rosy did not talk to anybody about the molestation, not even to aunt Trees. She fled the house as often as she could. She remembered B. pushing her in the hallway closet one time to 'feel her up.' Because she resisted, he became so angry that he tore off and broke Rosy's necklace with a Maria pendant. To this day, Rosy wears the pendant. It was not until she started dating Connie, a boy next door, at age seventeen, that the abuse finally ended.

Rosy, now: 'He was such a horrible man!' She thinks that during the war, he was completely siding with the Germans. She remembers how he drew little figures wearing a square cap. Next, he would draw 2 letters 's' on those caps. Only afterwards, she heard about the SS and grasped the meaning of those drawings. One of B.'s sisters

later told Rosy that he used to go to Germany as a boy and went up to the Russianborder with the German army.

When they went out, she sometimes overheard remarks such as: 'You hear that? She is black and she speaks dialect.

Like most miners' daughters, after finishing elementary school, Rosy attended home economics school. Miners' sons went to technical school, while children of mining officials would attend secondary school. Rosy was very athletic. When she was ten, she joined handball club Limburgia. She trained together with the men and was an exceptional player. 'I wanted to show I was good at something after all,' she said, 'so I used to train zealously.' She had a fun group of friends and with them she would go to 'house parties' in Brunssum or Treebeek. When they went out, she sometimes overheard remarks such as: 'You hear that? She is black and she speaks dialect.'

When she was eighteen, Rosy managed to leave home. She enrolled in a school for family care workers in Sittard and moved into its dorm. Her diploma was handed to her by Bishop Moors, who taught religion at the school. She remembers that during those lessons he would tell the students that the use of contraceptives was strictly forbidden. 'Well then,' Rosy said, 'that is why I had four kids by the time I was 27.'

One of those horrible nuns, with a large headpiece, told me it was a boy. I was allowed to look at the baby for one second before she took him away.

Mother Roos and stepfather B. had to wait a long time before they had a child together. The first time Roos miscarried, she called Rosy. Mother was standing in a pool of blood, and Rosy rushed out to alert B. in the mine. This happened three more times until mother, in 1965 at age 43, gave birth to a son, Harrie. Rosy was nineteen. Mother wanted Harrie's half-sister to be his godmother. Rosy was very happy with her baby brother, and her mother and she took care of him together.

Later on, when Rosy was a family care worker specializing in socially disadvantaged families, she realized that her home situation had not been all that different. Most of the time, her mother and stepfather were sitting at the living room table, an ashtray overflowing between them. They used to play cards with friends and relatives. Rosy tried to make some changes based on what she had learned during her studies, but without any results.

On May 31, 1966, Rosy and Connie got married at city hall, followed by a church wedding on June 22. The bride wore white, even though she was pregnant. Connie, who by then was eligible for military service, moved in with her, into the tiny bedroom in her mother's house. After five months, the pregnancy ended in a miscarriage. Rosy remembered how she went to the hospital with Connie, in a taxi. Connie had to leave because he had to report to the barracks. Not much later, the baby was stillborn. 'One of those horrible nuns, with a large headpiece, told me it was a boy. I was allowed to look at the baby for one second before she took him away.'

At age twenty-one, Rosy and Connie had their first child, Belinda. They were now living in their own apartment in Brunssum. Three more children followed, Maureen, Mahalia, and Emiel. Rosy obtained quite a few certifications, and found great satisfaction in her work in family care. She did most of the household chores herself in their small apartment where the six of them were living. Her husband was a musician and he was on the road a lot. She enjoyed her family life, and her work. Things seemed to be fine, even though one of the daughters left home when she was thirteen. She went to live with a boyfriend's family, because she thought her home life was not very cheerful, and because the other family lived closer to school.

All in all, Rosy's unknown parentage, her childhood, and the abuse she suffered, put a great strain on her. But as long as she kept busy, she was fine. She did not need to look back and she had no time to look ahead. Then came the moment the small flat in Maastricht was exchanged for a spacious detached home in a neighboring village. At first, her children were bullied. 'Blackhead!' kids would yell at them. Rosy instructed her kids how to respond: 'Go back to those bullies, talk to them and explain to them why you don’t like being shouted at.' The bullying gradually ended, especially when the people in the village understood that her father, Connie, was a famous musician. In those days he played with the popular band The Walkers. In 1971, they had a big national and international hit song, There's No More Corn On The Brasos. It was a traditional song, brought to America by African slaves.

Eventually, the children became independent one by one, and Rosy fell into a deep black hole. Rosy: 'When the kids started to go their own way, and Connie was on

the road most of the time, I felt worse and worse. I was living in a great house, had a lot of friends, more than enough money, and I was so gloomy. Every day, I felt more and more burdened. I no longer wanted to live, I had nothing left to live for.' She was in her late thirties. 'The worst thing that had happened to me and that had done so much harm, was the way my stepfather had treated me, not only the repeated humiliations, but especially the sexual abuse since I was nine years old.'

Even though she was in her late thirties, she had recurrent anxiety attacks. She was terrified of dark, enclosed spaces.

Rosy attempted suicide. She was admitted to the psychiatric ward of Annadal Hospital in Maastricht. Often she could not sleep at night, and she would get out of bed and go to the night nurses' room. A kind psychiatric nurse would get her through the night and comfort her. His name was Huub Schepers, the same Huub who later on had his story published in de Volkskrant. Meanwhile, Connie was taking care of the family with the help of a family care worker.

After that first hospitalization, Rosy decided to go look for her roots. She wanted to know who her biological father was. She consulted with people from the TV programs DNA Unknown and Without a Trace, but she pulled out when they proposed to get on TV with her story. She learned that Henri Brandon, the man from Surinam, had passed away. In the court papers from that time, she found information about his family in Surinam. Rosy made a trip to Surinam with her eldest daughter, who had married a Surinamese man. The moment she got off the plane at Zanderij Airport and was welcomed by her son-in-law's family, her emotions got the better of her and Rosy burst out in a flood of tears.

When she was around fifty, she went to her brother Harrie's birthday. By that time, mother was living with Harrie and his wife. Her sister-in-law said to Rosy: 'Mom wants to tell you something.' When Rosy went into a small spare room with her mother, she thought: 'This is it!' But all mother said was: 'A black American soldier grabbed me in the woods next to our house. I was pregnant right away.' She did not remember his name. Mother Roos died in 2002.

Rosy's children are not white Limburgers, they have darker skin. Daughter Maureen tells how people react to that. Recently, someone yelled after her: 'Moroccan!' And when she was in line at a window in city hall the other day for some formality regarding her work, an official pointed to another line, saying: 'Foreigners over there!' Her response, in Maastricht dialect, was: 'What do you mean, I'm from Maastricht, can’t you see?' She filed a complaint, apologies ensued.

Rosy met Huub Schepers again in October 2015, the psychiatric nurse who had been such a comfort to her more than thirty years ago. At that time, Huub kept his own story to himself, even after Rosy told him, during their nightly talks, how much she missed having a father. When she asked why he did not let on he had a similar background, Huub answered: 'I felt I should not burden you with my problems, I was there to help you.'