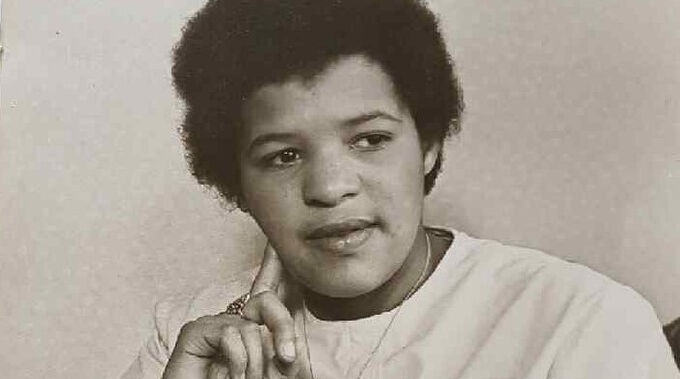

Wanda van der Kleij

Wanda Dera was the eleventh child of a Polish couple who had fled Poland in the First World War. Her father worked in the mines in Limburg. Following the heady days after the liberation, everybody in the village of Nieuwenhagen celebrated the liberation, including Wanda Dera. In September 1944 the Americans were stationed in Nieuwenhagen and Wanda Dera fell in love with Edward Brown, an African American soldier. They used to meet at her place above the local butcher shop. On February 7, 1945, Brown’s division moved on to Germany. The lovers said goodbye to each other before Wanda found out that she was pregnant. It was unlikely that Edward would ever hear the news. But Wanda would not be a single mother as she was already married to William van der Kleij.

When the liberators arrived, William was not in the village. It is thought that he was working for the Germans. He was originally from The Hague and it is said that young men from The Hague were rounded up during a raid in 1943 and put to work in the Limburg mines. When he did come back, Wanda was heavily pregnant. He was then sent to Indonesia in September 1945 as a professional soldier. Three weeks later she had a baby girl, the love child of Edward Brown. The baby was registered as Wanda, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Van der Kleij-Dera. William was not aware of the baby’s natural father as he wrote to Wanda saying he was looking forward to seeing ‘our girl’.

Van der Kleij returned from Indonesia when little Wanda was two and saw her for the first time. He saw her dark skin and realized he was not her biological father. He never forgave his wife and was always rather brusque and dismissive of the little girl. In 1947, the Van der Kleij family left for the Dutch East Indies for three years. Upon their return in 1950, and living in Maastricht, mother Wanda was pregnant with her first son, after whom they had two more sons, Wanda’s half-brothers. The parents divorced in 1985.

When Wanda was a child, one of her mother’s brothers emigrated to the United States. In the fifties, he proposed to his sister to adopt Wanda. He had only one child, a son. And, after all, wasn’t she an American? Wanda senior was adamantly opposed. In the family there was a ban on discussing little Wanda’s ancestry.

When she was in elementary school, Wanda started to realize something was not right and she was different. She did occasionally ask why she was darker than her brothers, but her mother would walk away without replying. ‘And after all,’ said Wanda, ‘we also had Polish relatives.’ At that time she did not know that Van der Kleij was not her father.

Recollections of her childhood were not pleasant. Wanda told us that her stepfather started sexually abusing her when she was a teenager. She was convinced her mother was aware of this, but turned a blind eye. Wanda was afraid to discuss it, but she did tell her mother her stepfather was hitting her. And again, the mother ignored her daughter’s accounts.

Hans Toonen, an editor at Dagblad De Limburger, together with his colleague Fietje Quaedvliegh, had started to track down Edward Brown for his ‘Quest for Fathers’ feature. In the June 20, 2001 edition, he wrote: ‘Forrest Lothrop, treasurer of the infantry division that had been stationed in Nieuwenhagen, told them from Sioux Falls, SD, that he had been unable to locate a co-veteran named Edward Brown.’ That could be because at the end of the war, African American soldiers who, as volunteers, were replacing fallen infantrymen were not all registered as such. Edward Brown must have been one of those volunteers.

At some everybody asking for information about their parents needs to fill out a form For Wanda, this posed a problem. Once she discovered that Van der Kleij was not her real father, when filling out answers about her father, she would write down the same information as for her mother. When answering questions about her parents’ hereditary particulars, Wanda would write she did not know because she was a liberation child. And invariably, people asked her to explain. ‘Very irritating,’ she said. Not much was known about her biological father. All she had were the words of a woman who lived across from Wanda senior during the time of the liberation: ‘Your father looked exactly like you, but with a mustache. He had a slight build and was not very dark.’

You do not have to go to school, because someone Black does not need to know anything.

Wanda did not get the chance to learn a profession. Her stepfather said, ‘You do not have to go to school, because someone Black does not need to know anything.’ Again, her mother looked the other way. In the end, Wanda was allowed to attend home economics school. After graduation, she got a job in community care services. Her professional life started off with a painful experience. When she rang the bell of the residence where she was expected, a woman opened the door, looked at her, and said, highly surprised: ´A Black?!’ and slammed the door in Wanda’s face.

When Wanda got married her mother-in-law asked a few times how she could be black while her brothers were blond. Wanda’s response: ‘No idea.’ On October 10, 1966, her daughter Birgitte was born. Many years later, Wanda and her daughter were going through some paperwork and came across Wanda’s birth certificate. Birgitte read that a midwife had registered Wanda’s birth with the Bureau of Statistics. ´Where was grandpa?’ Birgitte asked. Wanda now: ‘I just was not able to tell her, because I did not know anything, right?’ The marriage to Birgitte’s father lasted until 1993.

In 1985, Wanda's mother and stepfather got a divorce as he was having an affair. ‘Finally,’ Wanda said. ‘That was something my mother should have done years earlier.’ Only then did her mother tell Wanda she was ‘of an American.’ Wanda junior and her mother had never been really close. All those times when Wanda junior got up the courage to ask a question about her biological father, she was met with silence. Moreover, her mother did not react well when granddaughter Birgitte, who was living with her boyfriend, happily announced she was having a baby. Wanda senior thought it was a disgrace for her granddaughter to become an unwed mother. Whereupon Wanda and Birgitte pointed out that Wanda senior herself had had ‘someone else’s child.’ The relationship between Wanda and her mother was not good to begin with, but was seriously fraught after that. The relationship never got back on track. Wanda's mother died on January 4, 2012.

Wanda describes herself as someone with a restless nature, someone who has lived a complicated life. She felt she was hit with a double whammy: her colored skin and the fact that she was an ‘illegitimate’ child. For years, Wanda was in therapy because of her stepfather's abuse, and to deal with her restlessness. She got married twice and divorced twice. She worked as a volunteer lobbying for the interests of people on disability.

Wanda recently met another partner. One day, in Maastricht. Wanda was waiting for the bus. A young woman, Maureen approached her. Maureen: ‘I couldn’t help but ask her if she too had an African American father, because she looked like my mother Rosy.’ Maureen and Wanda exchanged phone numbers, and every now and then they sent each other text messages. Maureen got Wanda involved with the oral history project. Rosy and Wanda became friends, the call each other ‘sis.’